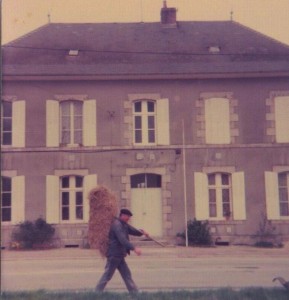

On the bus to Normandy, once again my friends and I battled the urge to close our eyes in sleep. Mrs. Correll resumed her patrol duty, walking the aisle, tapping shoulders, urgently entreating us: Wake up! Dont’ miss the beautiful French countryside! As soon as I noticed the loveliness of the landscape we were passing through, I had no more trouble fighting drowsiness. This was the idyllic countryside of fairy tales: rolling hills, pastures and fields neatly enclosed by fences and hedgerows, small cottages, many with thatched roofs and ivy-covered stone walls, the occasional grand manor house. The chic Parisians had disappeared, replaced by timeless country folk engaged in timeless pastoral activities, like the farmer above, carrying a hay bale on his back. We saw French sheep, horses, cows and dogs. They looked somehow more charming and worldly-wise than their Georgia or Kentucky counterparts. It was cold outside, but the sun was bright and the land was poised for the greening of spring.

The drive took nearly four hours. We shared the bus with a larger group of high school students from the north Georgia town of Chickamauga. The French countryside evidently held little charm for them. Restless and bored, they whiled away the time by pining for the far-away, all-American life. They bemoaned the typically much-missed delights: juicy hamburgers, thick steaks, “real” toilet paper, cold Cokes, water with ice. Mrs. Correll had made it clear to us well before the trip that if we uttered such clichés we would risk her wrath. She would not hear us talking like ugly Americans. We were a sophisticated group, she stressed. We knew we weren’t especially sophisticated, but we didn’t want to disappoint the teacher we revered. Seeing the Chickamaugans behaving boorishly inspired us to try to act cultured and urbane. We considered them to be country bumpkins. I’m sure they thought of us as annoying little city twits.

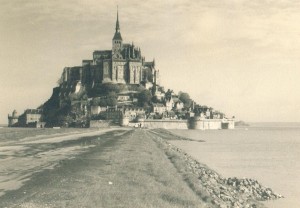

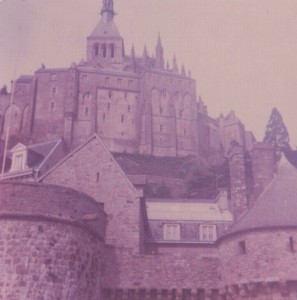

My first glimpse of Mont St. Michel was magical. I was not alone; the vision was sufficient to switch the Chickamaugans’ attention away from the pleasures of home. I’ve returned to Normandy twice over the years, and each time, the initial sighting of that towering castle-church on the rock, rising out of an immensity of flat sand, retains its unique power.

According to medieval texts that recount the beginnings of Mont Saint-Michel, in the eighth century, the archangel Saint Michael appeared in a dream to Aubert, Bishop of nearby Avranches. He commanded Aubert to build him a church upon the rock. When difficulties arose, as one might expect with such a tricky architectural undertaking, the archangel was said to have worked miracles that allowed building to continue. Aubert’s church was consecrated in 708, and word spread of the majestically situated church divinely ordained by an angel.

By the twelfth century, Mont Saint-Michel had become one of Europe’s premiere pilgrimage destinations. In an age that valued visible, tangible relics of a saint’s earthly life, an angel might seem an unlikely candidate to become a popular pilgrimage saint. Saint Michael, a heavenly creature who never dwelt on earth, could offer no bones, blood, hair or instrument of torture to be venerated. But Aubert and those who succeeded him in tending the shrine were creative and enterprising; if the people wanted relics, they would have relics.

Some pilgrims may have come for the relics. Probably more came to soak up the romance of the place itself. Its exceptional location and the drama inherent in the site offers its own enchantment. Thrill-seekers made the pilgrimage because it entailed risk and adventure. Getting to the church on the rock meant navigating the bay’s capriciously shifting sands and the rushing tides that transformed the mount into an island twice daily. There was also the danger of losing one’s way when the thick fog settled in.

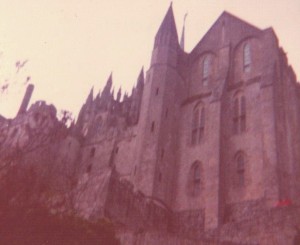

A series of fires required sucessive rebuildings. With each disaster, reputed miracles were interpreted as proof of Saint Michael’s continuing support. He had not abandoned the site. On the contrary, he required a bigger, taller church. The Benedictine Abbey that stands today was begun in 1023. While portions of this Romanesque building remain, most of the church dates from the Gothic period. The archangel was traditionally worshipped in high and lonely spots, and the church that evolved over the centuries might be seen as a sort of architectural portrait of Saint Michael. The building’s massive heaviness and its apparent unity with the rock reflect the military saint’s enduring strength, while its soaring height stretches toward his heavenly domain. On stormy nights, as lightning struck, wind howled and thunder rumbled, the medieval faithful claimed to witness the archangel’s battle with Satan at the top of the mount.

That chilly April day in 1975, our group hadn’t had to brave the elements to reach Mont Saint-Michel. We weren’t exhausted from months of walking in all weathers and through difficult terrains. But we were tired of sitting, and delighted to get off the bus. As we hurried along the causeway, a few of us may have been nearly as excited as some pilgrims before us. The view of the mount retained its drama even at close range. Winding our way up the narrow, cobblestoned street, the adventure continued. The story-book town, with its tightly packed medieval buildings, the upper levels jutting out above those below, was quaint yet scruffily authentic, not a plastic Disneyesque quaint. Inside the church, the shadowy crypts, cut into the depths of the rock, were austere and fortress-like, making the soaring nave, with its pointed Norman arches and tall clerestory windows, appear all the more gloriously luminous.

Dusk was approaching as we climbed to the top of the ramparts to look out over the vast expanse of sand and sea below. The wind was picking up. There was no lightning, but the atmosphere felt charged. That night, we did not see Saint Michael engaged in a furious war with the devil, but the possibility didn’t seem at all far-fetched. What a spectacular sequel to our Super-8 movie Dark Secrets we could have shot at Mont Saint-Michel!