With the ceremonies attending this month’s 75th Anniversary of the D-Day Invasion, my Uncle Bill, a veteran of World War II, has been very much on my mind. Bill wasn’t among those who stormed the beaches of Normandy. Instead, he was a Frogman in the Pacific. But were he alive today, he would have been 93, the same age as many of the veterans who returned to the French coast last week to be honored for their long-ago heroism. Like these now elderly, frail gentlemen, during his military service, Bill persevered in the face of daunting odds and certain danger. Like them, he would likely look back today and marvel at his youthful naivete, fearlessness and fortitude. Also like these aged honorees, he would probably contemplate the accident of his own survival as he recalled friends who were not so fortunate.

It seems fitting, then, to repost an amended version of a tribute to my dear Uncle Bill, written during Father’s Day week in 2012.

William Graham was born in rural Marion County, Kentucky in 1925, the third of five children, the second of my maternal grandparents’ three sons. My mother, the baby of the family, would enter the world ten years later. In physical appearance, temperament and attitude, Bill was very much like his father, who died when I was almost six. For me, Uncle Bill provided a tangible, very real link to my grandfather. (See my earlier post here: A Week of Good Fathers: My Grandaddy. For that reason alone, I would have revered him. For many other reasons, I loved, and loved being around my Uncle Bill.

By all accounts, Bill was so like my grandfather that they were often at loggerheads during my uncle’s boyhood and teen years. Each was painfully honest in every situation, and this may have proved more of a stumbling block than a stepping stone in their relationship. Bill had little interest in becoming a farmer like his father. Fortunately for him, his older brother Leland had followed in Grandaddy’s footsteps and taken over the cultivation of the land by the Rolling Fork River. My grandfather continued to maintain the farm closer to town. When World War II began, Bill saw it as an opportunity to escape farm work and put a stop to conflict with his father. He enlisted at seventeen, just before Christmas of 1943. Although blessed with a keen intellect, a rebellious streak led to conflicts with teachers, and Bill left for the Army without completing his senior year of high school.

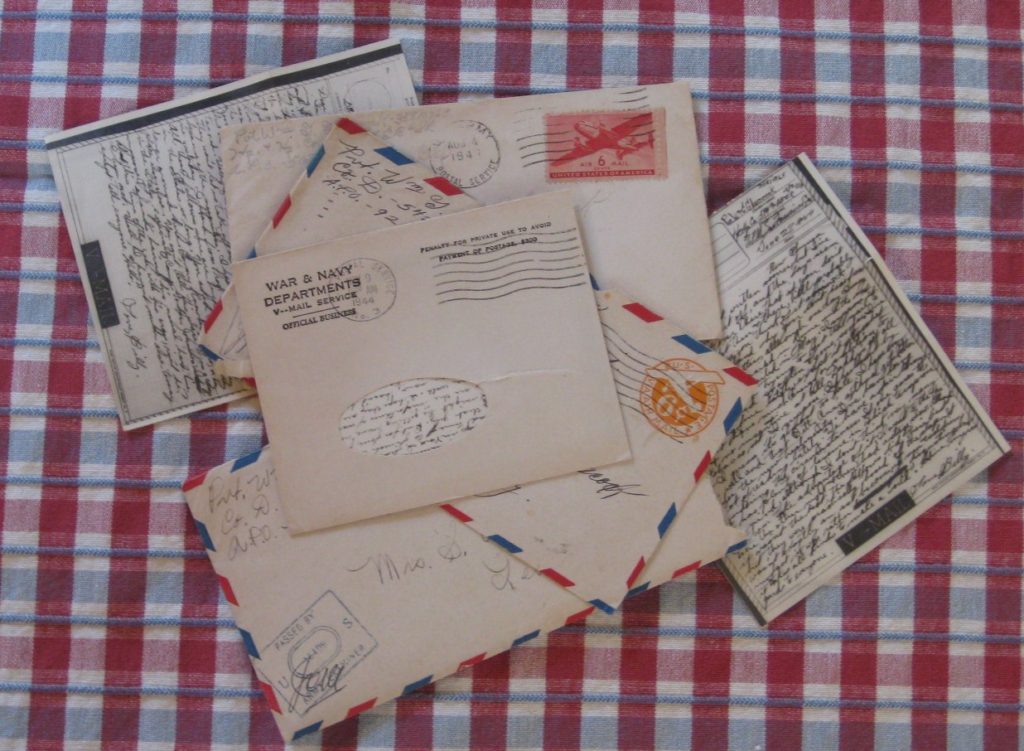

Bill wrote home diligently throughout his military service, and we have most of the letters he sent. Never overly sentimental, never self-pitying, his early letters border on heartbreaking. They express the thoughts of a young man who acted in haste and immediately regretted his decision.

These first letters, sent from Fort Thomas, Kentucky, tell of receiving vaccinations, shoveling snow in blizzard-like conditions, and hoping to join the Air Corps but being eight pounds underweight. Bill lists the various articles of clothing he has been issued, remarking with amazement that it’s more than he’s ever seen before. He asks his family to send some shoe polish, because his boots have stiffened uncomfortably from daily wear in the snow and slush. He also asks for a pencil and a few wire coat hangers. The talk in the barracks, morning and night, was that of homesick young men pining for their loved ones and the lives they had left behind. Most, like Uncle Bill, were from rural areas. They had realized, too late, the simple glory of farm life. In Bill’s words, he “never realized how swell home was, but he sure would like to see it now.” His father, he admits, knew more about the Army than he did. His letters are always signed “Love, Billy.”

He was soon transferred to Fort Gordon-Johnston in Florida for basic training to enter an amphibious brigade. At the end of January 1944, he reports getting $39.55 for his first month of duty. Nearly every letter begins with an apology for not writing sooner, but he seems to have written every few days. He often asks about my mother’s asthma, the progress of the tobacco stripping, and he offers hopes that the crop will bring a good price. A high point about army life, he notes, is access to new movies. He mentions seeing Jack London, Swing Fever and later, Double Indemnity. In one letter he writes that he was “feeling fine, and at times, almost happy, but not quite.” That expression of thoughtful, measured restraint is so very Bill.

As the months ticked by, Bill wrote from increasingly exotic places, although his exact location could not be divulged. From Florida, he went to New Guinea, the Dutch East Indies, many small islands in the Phillipines, and then on to Hawaii for training in Underwater Demolition. After his return, he talked of being dropped in the ocean, no land in sight, and no special equipment but a pair of flippers. He and his fellow Frogmen were expected to tread water for six to eight hours as they awaited the ship’s return. The Frogmen were the precursors to the Navy SEALs, and I can only imagine the intensity of other training exercises and actual duties. Bill didn’t talk much about any of that.

The tone of homesick regret is gradually replaced by a sense of wonder at the strange beauty of places he could never have imagined. In the Philippines, he buys a handmade mattress from a local woman, tours a ruined city in a horse-drawn buggy-taxi, attends Saturday night dances on base where the “fine-looking” Spanish and Filippino girls “can jitterbug to put the girls back home to shame.” He discovers an injured cockatoo in the jungle and nurses it back to health. He revels in the abundance of tropical fruit and notes that there is no cigarette shortage in the army, unlike in the States. He is surprised by his ability to work all day, on a ship in the equatorial zone, in temperatures up to 115 degrees, with hardly any ill effects. The miserable poverty of some of the native villages affects him deeply. Hospitalized for a while with “yellow jaundice,” he enjoys the rest, as well as the fluffy pillows. When a fellow patient has a break-down and runs screaming in the halls, he remarks that the jungles will do that to you, after two or three years. He laments not being able to write about the most interesting parts of his days, because such information would be censored. Despite his discretion, in several of his letters a line or two has been neatly cut away. How I wish I’d read these letters during Bill’s lifetime. There are so many questions I would have asked.

In Bill’s letter of August 16, 1945, news has just broken of Japan’s surrender. The war is officially over. He begins to believe he will return home soon, to the farm he had so wanted to leave. After several months in the U.S. occupational forces in Japan, he arrived stateside in the winter of 1946. Like his fellow soldiers lucky enough to return, he was older and wiser, and had a renewed appreciation for home.

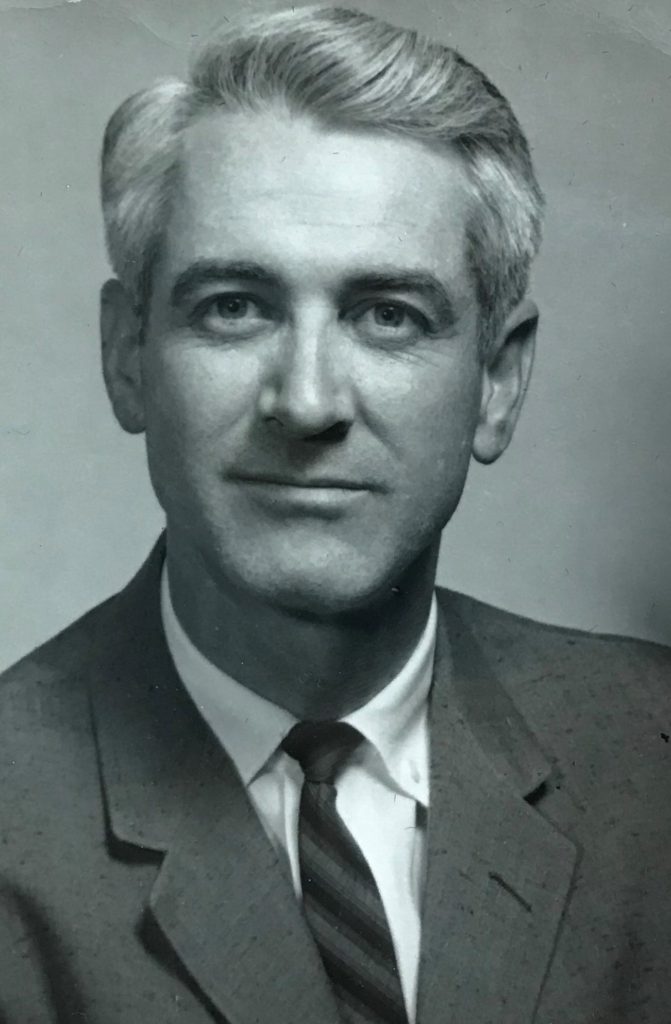

Bill went to the University of Kentucky on the G. I. bill. His dark hair turned completely silver when he was still in his late 20s, giving him an air of elegant sophistication. My father, seeing Mama with her brother on campus, assumed she was with a handsome professor. Bill was in his 30s when he married a divorced woman with two sons. Margaret was the sister of one of my mother’s childhood friends. Bill never had any biological children, but he was a supportive and caring stepfather. Mama and Bill were close, and they were alike in many ways. As long as I can remember, Uncle Bill was a big part of my life. He often traveled to Atlanta on business. When it was still a rather grand hotel and hadn’t slipped into seediness, he stayed downtown at the old Henry Grady Hotel. He often had a free evening, and he’d treat my parents and me to a festive dinner, somewhere we wouldn’t ordinarily go. Occasionally he stayed at the now long-demolished Admiral Benbow Inn on Spring Street, which had a pool. I remember swimming there a few times with my two best elementary school friends. I always looked forward to Uncle Bill’s visits. I loved his dry wit, which was sarcastic and sometimes biting, but never mean-spirited. He was well-read, reflective, widely informed and inclined to doubt. He shared with my mother and me a love for the melancholy humor of Thomas Hardy novels. As a connoisseur of life’s ironic absurdities, Bill was highly amusing company.

Uncle Bill was empathetic and attuned to the plight of the down-trodden. He was especially soft-hearted when it came to animals. (I sure wish I could have learned more about that injured cockatoo!) Bill always had a dog, or he cared for someone else’s dog, typically one that would prefer to be Bill’s. When a neighbor’s three-legged lab mix made it clear that he would much rather live with my uncle, his owners passed him on. With Bill, Colonel got several walks each day, plus a long car ride. Colonel loved a ride, so Bill made it part of their routine. During a visit after Colonel’s death and not long before Bill’s own, I went with him on his nightly duty to walk a neighbor’s dog. Bill had noticed that the dog’s owner worked long hours, and he offered to provide an afternoon walk. Before long, this had turned into three daily walks. Bill was retired and dogless at the time, so he was happy to oblige. On the night I went with him, he put his raincoat over his pajamas and we walked down the street to the neighbor’s home. He let us in with his own key, and the woman rose to greet us warmly, from what appeared to be a late-night dinner party. No doubt her guests thought it odd that her dog-walker was a dashing silver-haired seventy-year old in PJs. No doubt they also thought she had lucked into a great deal. Bill never cared if people considered him somewhat eccentric.

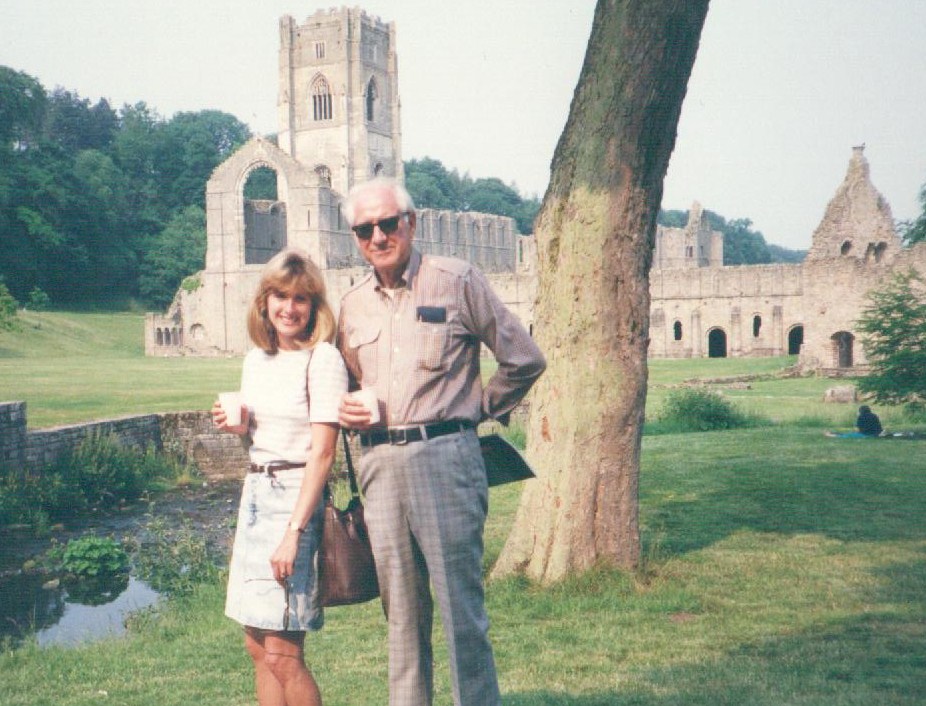

Bill’s time in the service may have fostered his love of travel. He and Margaret were always setting off for some legendary spot. During my year in England they popped in on several occasions. Our pre-dinner pub conversation was always a particular pleasure. They were my first visitors when I lived in Cambridge. We ate at the city’s best restaurants and took day-trips to Eton and Windsor Castle. Later in the year, we rented a car and drove up to York over the course of nearly a week. Bill and Margaret went on to Scotland and I returned to London by train. And when I was in England for a month the next year, they came back, too. I can still see the look of incredulity on Bill’s face when he saw my tiny, cell-like room in the London House Annex, a dormitory for visiting students.

Uncle Bill died much too soon, at 71. I guess because he was so like my grandfather, who made it to 79, I thought we’d have him around for a few more years. He was there for my wedding, but he never got to see my beautiful baby girl. He would certainly have enjoyed watching her grow into the unique young woman she is now. It’s a great consolation, however, to reflect on the many lives that Uncle Bill touched, with his kindness, generosity and humor. And I have faith that now, in some heavenly realm, he and Grandaddy, two kindred spirits, are enjoying peaceful, yet lively good fellowship.

What an excellent tribute. I’ll bet Uncle Bill had some great stories.

Thanks, Janice! Bill did have many good stories. But like many veterans, he rarely talked about his time in the service. I wish I could have persuaded him to tell me more about those years.