My mother’s father was the only grandfather I knew. Daddy’s Dad had died young, many years before my birth. Mama was the baby of her family, the youngest of five children, and her parents were in their 70s when I was born. I didn’t have much time with Grandaddy, because he died just before I turned six. But he was a warm, powerful, dignified presence, and he left a strong and lasting impression. My grandmother lived on in good health for nearly another 20 years, and through her shared memories and our own, he was very much with us.

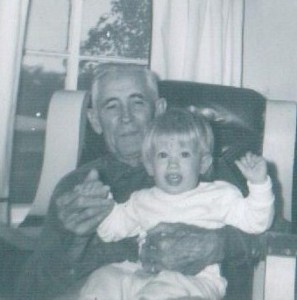

Here, in Grandaddy’s lap, I’m about a year old. We’re in the big creaky rocking chair that was a fixture in the kitchen of my grandparents’ farmhouse. The chair was painted white and had red leather upholstery. It reminded me of Santa’s sleigh and carried with it all such pleasant connotations. When I think of Grandaddy, I usually envision him sitting in his rocking chair, reading The National Geographic or The Saturday Evening Post. He was an avid reader. We have some of the beautifully bound books he read as a boy, such as his beloved James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, inscribed with his name in brown ink in a graceful, elegant script. Stories abounded of my young grandfather’s attempts to carve out undisturbed reading time. Avoiding his younger brother Joe required daring and ingenuity, so Grandaddy read in trees, on roofs, in the recesses of various outbuildings, or far out in the fields. His power of concentration was legendary; when he was reading, he was often oblivious to the goings-on around him.

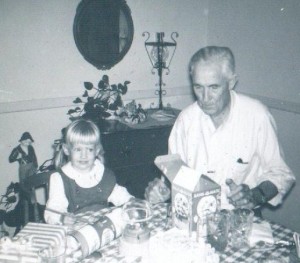

My grandparents were visiting here at our first house in Lexington on the occasion of my second birthday. (Note the gifts of Tinkertoys and a toy gumball machine.) Grandaddy looks a bit bored; no doubt he would have preferred to be home in his rocking chair, reading. But I didn’t notice at the time. I was always completely certain of Grandaddy’s love, which he demonstrated in quiet, unassuming ways. With a heavy pat on the back, he called me his Little Buddy. I was thrilled to be his Little Buddy.

On the day after my party, in Mama’s arms and pouting, I was sad to see my grandparents leave. Grandaddy is dressed for the drive home, wearing his signature summer straw hat. He was a tall, broad-shouldered, stately man, dapperly dressed at all times.

Grandaddy was a farmer. During the Great Depression he had managed, with grit, thrift, determination and some good luck, to keep his two farms solvent. He owned the land around my grandmother’s birthplace, up in the knobs by the river, as well as a large parcel much closer to town. Tobacco was his primary cash crop. Just as tobacco saved much of the South after the Civil War, it got my mother’s family through the lean years of the 1930s. When I was a child, Grandaddy still went out into the fields nearly every day, at least for a short while. He never wore the overalls favored by many farmers of his generation. His neatly pressed everyday uniform consisted of belted khaki pants and a plaid cotton shirt, always worn with the collar buttoned. Clint Eastwood dressed similarly in his film Unforgiven, and the resemblance he bore to Grandaddy was almost eerie.

In this photo, I’m with Grandaddy and my aunt, just back from church. I felt like a big girl when I accompanied my grandparents to Sunday School at the pretty little Methodist church in town. My parents usually met us later for the worship service. Grandaddy’s trusty old Dodge can be seen in the garage that adjoins the smokehouse at the back left.

My grandfather died after a stroke at the age of 79. I remember the pressing crowds at his funeral, the flowers everywhere, my uncles, aunts and cousins milling around, the abundant snacks served continually in a back room at the funeral home. I wore a pale blue dress and black patent Mary-Janes. As I mentioned in an earlier post (Memory, Persistently Disintegrating and Rebuilding, January 2012), I seem to recollect kissing Grandaddy as he lay, as still as a granite monument, in his coffin. The firm iciness of his cheek was a shock. There were many tears, but the atmosphere was not one of abject sadness. Perhaps because my grandfather was, in all things, a man of honor and integrity, there was the sort of comforting satisfaction that attends the close of a fairly long life, well lived. There was the certainty that through this one life, many others had been enriched. We were better for having known and loved him. We would cherish his memory like a treasure, throughout our lives.

Grandaddy’s death marked the end of an era. The big white frame house and its surrounding farmland were sold. My grandmother moved to the center of town, where she had a spacious apartment at the top of another grand old home. I liked her new place, but I felt the loss of the farmhouse and its land very keenly. For years, my dream was to get rich somehow as an adult, return triumphantly and buy it all back. As smaller houses popped up nearby, I fantasized about buying and demolishing them, so the old house could stand once more as it was intended, alone amidst the broad fields.

One day it hit me that those houses, small 1960s ranches, were the well-loved homes of families, just as my grandparents’ house had been. With this realization, the need to get back “what had been ours” became less acute. But ever since the day of the sale, I’ve grappled with the loss of the house and the land. After all these years, I can say that I’ve almost come to terms with it. I’ve grasped the truth that no property is ever truly owned. If we’re lucky, we have the chance to be a steward of a place worth preserving for the future. Still, change is inevitable, and nothing of this earth lasts forever. What really counts is how well we manage our stewardship, how effectively we deal with the changes to come, for our own sakes and for that of the community around us. My grandfather was a thoughtful and caring steward in all that he was given. I try to be a good steward of his memory.