My friend and former boss Gudmund Vigtel died last month at the age of 87. For nearly thirty years, Vig, as he was generally known, was the face and guiding force of Atlanta’s High Museum of Art. He became the museum’s director in 1963, when it was a fledgling institution in a provincial backwater, housed in a nondescript building adjacent to its first home, the Peachtree Street mansion of the High family.

Vig led the High through two pivotal periods of extraordinary growth. In June of 1962, 106 of Atlanta’s most prominent arts patrons, returning from a museum-sponsored trip to Europe, were killed when their plane crashed on take-off at Orly Airport in Paris. Since Atlanta’s founding in 1836 as Terminus, the end point of a railway hub, its citizens have tended to value business over culture. But they are a resilient lot, determined not to be bested. The Orly tragedy, like General Sherman’s burning of the city during the Civil War, inspired a deeply felt resolve to regroup and rebuild, bigger and better. Gudmund Vigtel, then assistant director at the Corcoran Gallery in D.C., was hired to head up the new, expanded arts facility to be known as the Atlanta Memorial Arts Center.

Vig must have stood out as a cosmopolitan, dashing European figure in the Atlanta of the early 60s. Born in Jerusalem to Lutheran missionaries from Norway, he had lived in Vienna and Oslo before his family fled (on skis, as I’ve always heard) from Nazi-occupied Norway into Sweden. But Vig had Georgia ties as well. Having studied art in Sweden, he received a Rotary Scholarship that first took him to a small college in north Georgia. It was not a good fit. He recounted how he spent lonely afternoons sitting on a big rock, asking himself, Why am I here? Before long, he managed to transfer to the Atlanta College of Art, where the more urban environment suited him better.

I met Vig during the second pivotal period of his tenure at the High. During the 1970s he became increasingly convinced that his museum was still too small. When, in 1977, the blockbuster King Tut show bypassed Atlanta for New Orleans because the High lacked sufficient exhibition space, it was clear that Vig was right. He launched an impassioned campaign for a considerably larger and more striking building. Despite the board’s initial preference for a local architect, he managed to persuade them to choose the as yet unproven Richard Meier of New York. Meier would go on to to design the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and to win the Pritzker Prize for architecture.

I had the good fortune to work for Vig as Secretary to the Director during the High’s first two years in the new Meier facility. (There are, of course no secretaries at the museum now, or perhaps anywhere; they have been promoted to other titles, if not in salary.) Thanks to my dentist, a family friend, avid art collector and museum patron, I learned about the job opening. It was the summer of 1983, and I had just graduated from UGA with a degree in Art History. I was coming to terms with the realization that this was, as I had suspected, hardly a golden key to a lucrative or, perhaps, any career. Luckily, I could type. I applied at the High. I wasn’t hired; there was a better, faster typist. About three weeks later, I got a call from the museum. The other applicant hadn’t worked out, for various reasons. When Vig had referred, for example, to the artist Botticelli in his dictated letters, this secretary had repeatedly transcribed Buddy Chelly. Was I still interested?

The postmodern Meier building, its undulating facade clad in white enamel tile, was due to open that October when I began work in July. The offices had just moved into the new quarters, but the galleries and atrium remained unfinished. Heavy plastic sheeting kept some of the dust out but did nothing to diminish the loudness of the construction noise. The pace of construction was quick and constant, and it only added to the excitement of working at the museum. I loved my front-row seat in the living theatre that was staging the airy new building’s completion. And I soon became fond of my boss and the rest of the museum staff.

Many of us spend our lives knowing and regretting that we have not yet hit upon the perfect career fit. Vig found his, it would certainly seem. He had a broad knowledge and true devotion to art of various genres and styles. But he lacked any trace of pretense or conceit; he bore no resemblance to the stereotypical artsy intellectual. Not a single aspect of the life of the museum was beneath him, and he was apparently tireless. What’s more, Vig had a real gift for the human connection; he was thoughtful, warm, empathetic, funny and charming. He inspired the best in every staff member, and we held him in high regard.

As Vig’s dramatic vision for the new building was nearing completion, it was a heady time to be part of the HMA team. The museum opened on schedule in October, with a dizzying flurry of celebratory events held in the soaring central atrium. Vig treated his staff with the same respect and courtesy as the most generous or sought-after patrons. HMA parties were equal-opportunity events. Security guards danced with curators; art handlers and secretaries rubbed elbows with Atlanta’s civic leaders and the occasional celebrity. Vig was always there at the heart of the party, like a joyful father of the bride, surrounded, in his elegant home, by those he loved best.

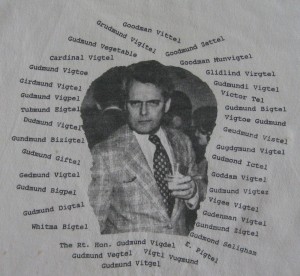

Vig’s oddly spelled Norwegian name confounded most homegrown Southerners. Yet its pronounciation was straightforward: Good mund Vig tel, with the accent on each first syllable. I was amazed by the vast volume of unsolicited letters (many of them very strange, to say the least) that the museum received. The majority of these erred comically in the spelling of Vig’s name. They variously addressed him as Gudmund Viglet, Gudmund Vigtoe, Goodmood Vigel, Goodood Wigtel and even, somehow, Tubmund Eigtel. Vig never took himself too seriously, and he found these permutations as amusing as I did. He also laughed and reassured me when I realized, too late, that one of the letters I typed had gone out to Ms. Roberta Goizueta instead of Mr. Roberto Goizueta, then the Chairman of Coca-Cola.

Vig’s impact on the arts of Atlanta was profound. Like so many others whose lives he touched, I will think of him often, and with affection. In my mind I see him now, and it’s 1985. He’s coming back from checking a new painting in the galleries, crossing the wide atrium. He’s walking his characteristically jaunty walk, grey curls bouncing a bit, suit slightly rumpled. As he approaches, I hear him speak my name in the Norwegian accent he never lost, and I see the customary twinkle in his eye. Gudmund Vigtel will be greatly missed, but lovingly and gladly remembered.

On this T-shirt, made c. 1985 by the HMA staff to celebrate Vig’s birthday, he is surrounded by some of the more egregiously erroneous misspellings of his name, collected from letters. Vig’s uncharacteristically gruff expression was intended for comic purposes. I wish I hadn’t worn the shirt for painting; the splotch on Vig’s jacket is a later, accidental addition.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading about your memories of Gudmund Vigtel! I had never heard of him before I read your story. The misspelled names on the T-Shirt are hilarious, especially one name on the right side! Just out of curiosity, I went to eBay to see if there was a Gudmund Vigtel T-Shirt for sale after you mentioned that your shirt had paint on it. I did not find the shirt but found something else which I will share soon.

Thanks, Dan! I loved working at HMA. It was a happy, comfortable work environment, with great people, a wonderful boss in Vig, and lots of nice art in the galleries that I could enjoy in my free time. For me, it was the perfect first job.