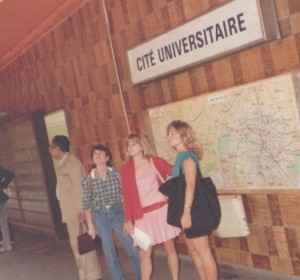

Returning after many years to a pivotal, memory-charged place verges on the overwhelming. That day at the Cité Universitaire, I could see the young college student version of myself overlaid with that of the middle-aged wife and mother I’ve become. Briefly, both versions coexisted, and it was unnerving.

I saw the stages of my life like a design done on multiple sheets of transparent plastic. An early layer shows me at nineteen, near the beginning of my stay in France. I’m at the desk in my room, writing a letter home. I’m aware of how fortunate I am to be in Paris. I had known it wouldn’t be the place of idyllic enchantment that the movies show. Still, I hadn’t expected to be quite so disenchanted. I’m surprised at what feels like borderline disappointment. My friend Jackie had participated in the same program the summer before, lived in the same building. She’d described the trip as a “blast.” I’m not having a blast, and it bothers me. I should have gone the year before, with Jackie. I feel petty and petulant. I almost wish I were back home.

I’m sheepish in my homesickness. I hate to admit it, but I miss my parents. I miss my dog. I miss my best friends. I guess I miss my boyfriend, although this recollection is less clear. I’m certainly disappointed that the local youths who trail us everywhere (and there are many, because we are obviously American, and they’ve apparently heard that American girls are supremely willing) are not exactly the cream of the crop. We’ve learned to pretend not to see them, to say nothing. If we look blankly through them, if we show no reaction, they usually go away. Some are more persistent than others. Some become belligerent. While we rarely feel truly afraid, it’s wearing to have to be constantly on guard. I know how the chickens in the henhouse must feel when a fox is on the prowl.

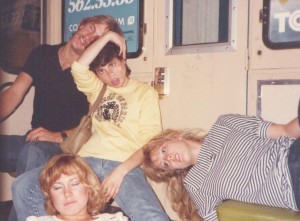

Another layer, toward the end of the trip. I’ve come to terms with Paris. So I didn’t have a blast every day. But there were far more fun times than bad. We’ve learned to feel at ease in the city. We understand the Metro. We’ve checked off the major tourist sites. We’ve discovered favorite spots we’d never before heard mentioned. I’ve worked my way through the Louvre, room by room. It was free on Wednesday afternoons, and I took full advantage. Often, up in the remote nineteenth-century galleries of French painting, it was just me and the guard soaking up the atmosphere of quietly magnificent landscapes by Rousseau, Millet and Corot.

We’ve made new friends among those in our group, become closer to those we already knew. We’ve had many laughs and some adventures. We’ve ridden in a little French car through Paris traffic. We’ve bicycled through a forest near Compiègne. We got locked in the historic Père Lachaise cemetery but managed to find our way out. Fending off local young undesirables has become second nature. And we did meet some perfectly nice local boys, had a couple of chances to sit at cafés speaking French with them, just as our textbooks had suggested we might. We discovered that four-franc wine was quite drinkable. We learned that the best place for our big group to enjoy an affordable, easy-going meal was an Algerian restaurant in Saint-Germain-des-Prés.

We were not wholeheartedly welcomed by every citoyen. But each time we experienced a stranger’s animosity, others followed with gestures of kindness. On Bastille Day, for example, waiting for the Metro at the Châtelet station, a drunken man took unexplained offense at my hair color. As I’d already noted, blond hair stood out in Paris, but it hadn’t yet provoked this sort of ire. Les cheveux blonds! Les cheveux blonds!, the man sputtered, pointing at my hair and approaching more threateningly with each exclamation. The French crowd muttered its disapproval, and a powerfully built, well-dressed man placed himself as a reassuring barrier between the man and me. Another night, when we found ourselves in an unfamiliar area after the last Metro had departed, a couple walked with us to the bus stop and waited until we were safely aboard.

In the photo above, I’m holding my only major purchase, a bust of a porcelain-headed lady decked in fur and feathers. She struck me as perfectly Parisian. Her current home is atop my piano.

By the time we were to leave for our two-week tour of the countryside and other notable French cities, I was almost sad to say goodbye to Paris. My early feelings of disappointment had vanished. Sure, the area around the Cité was a little messy. But all in all, the city was more beautiful than I had remembered it seven years before. And as for the French people, well, they’re people. My friends and I had often been amused by the cultural differences we observed. Why would the French do this, or that? Why not the American way? Isn’t that funny? But fortunately, we had come to realize that these differences are, in truth, unimportant.

The variety of surface details from culture to culture gives life interest and humor. But at a deeper level, we’re more alike than different. Warmth and good will need no common spoken language. They transcend all barriers. Our summer in Paris had helped us learn perhaps the most important lesson of travel: the ties that bind us as humans are stronger than the forces that pull us apart. Of this truth, travel offers living proof.