Standing in the garden of the Cité Universitaire this past April, below the room that served as home during my college summer in Paris, I felt like I was in a time warp with tunnel vision. I could reflect on successive Paris life layers at once, one atop another. Today’s post concerns a time thirteen years after my travels in France as a grad student. It’s 2002. For the first time, I’m in France and I’m not a student. It feels strange. The responsibilities of adulthood have caught up with me. I’m a wife and mother, here in the city with my husband and my parents. We’ve left our nearly three year old daughter at home with H’s parents.

It had long been a goal of mine to accompany my parents to France. During my year in England, we had traveled together for three weeks, but we hadn’t yet done France. In the spirit of parental sacrifice, Mama and Daddy had repeatedly stayed home and paid, or helped pay my way. We had always said Sometime, we’ll all go. That sometime seemed to have arrived in 2002. We were all healthy and ambulatory. H, like me, was eager to return to France. Fourteen years had passed since his semester in Rennes. The overlap in the timing of our European student adventures had provided us with a point of commonality that may have been crucial in drawing us together initially. (See That French Connection, April 2014.) Ever the dutiful son-in-law, H didn’t complain about traveling with his wife’s parents, or sharing the tour-guide obligations.

Our daughter was old enough to understand that we weren’t leaving her for good. H’s parents were willing and able to care for her. Very briefly, we considered taking D with us. But I could see how the trip would unfold. She’d be continually preoccupied with something that seemed totally inconsequential to adult eyes. Under the fascinating spell of fallen leaves in the dirt, she’d be oblivious to the historic splendor all around her. My entreaties would go unheard: Look up, sweetie! Look at the beautiful towers. See those funny creatures way up high? Those are gargoyles. My mother would miss most of the sights she’d anticipated for so long. In an effort to make the trip proceed more smoothly for the rest of us, she’d devote her attention to placating her granddaughter. I’d feel guilty. We’d all be testy. Best to leave our toddler with Grandma and Grandpa at home, where she could enjoy, unimpeded, the pleasures of domestic leaves and dirt.

My objectives for travel abroad have varied according to the stages of my life. As a student wearing the rose-colored glasses of youth and freedom, the realm of possibility was vast. Who knew what adventures, what fulfillments of fantasy lay ahead? Caprice, romance, astounding coincidence–while I didn’t take such winged creatures as my due, I also didn’t rule them out entirely. Who’s to say absolutely that I would not meet a sensitive, handsome young man as we admired the same obscure, underappreciated painting in the Louvre? Was it utterly impossible that he’d be involved in the thoughtful restoration of his family’s ancient and immense château? That my fresh American sensibility would invigorate him like a breath of fresh air? That we’d fall in love and live happily ever after among the rose-blanketed walls of honey-colored stone? That the surrounding village would be peopled by delightfully eccentric and charming characters, who would hold us particularly dear as Lord and Lady of the Manor? Such a scenario was clichéd, antiquated and extremely unlikely. But it wasn’t entirely impossible. After all, I was young. Anything was possible. And I’d experienced the unlikely before.

On this trip, it’s a different story. As a no longer young adult traveling with my husband and parents, my goals are considerably more modest and down-to-earth. I’m looking forward to seeing my parents appreciating my favorite French sights, and to comparing student experiences with my husband. I’m hoping for beautiful scenery, comfort, the avoidance of injury, illness and mishap. While my parents are hardly frail or weak, they are, obviously, even less young than I. A successful visit will be free of emergency room visits, crippling accidents, assaults and major transportation breakdowns. It will mean not losing Mama or Daddy temporarily or permanently on the Metro. Perhaps most importantly, it means an uneventful return that brings us back home safely to our little daughter.

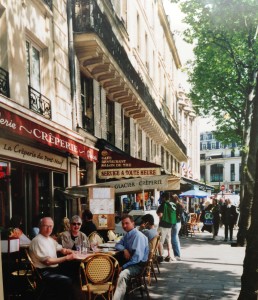

Without incident, we check off the sights my mother the history buff had been waiting years to experience: Notre-Dame, the Sainte-Chapelle, the Louvre, Versailles, the Arc de Triomphe. (Daddy is sunnily content to go wherever she, H or I suggest.) We avoid misadventure but find ourselves on its heels several times, as when we stumble upon the aftermath of a purse-snatching and the apprehension of the thief. My parents are hardy, adaptable, unfussy travelers. They don’t even grumble when, after wandering the Versailles gardens and Marie Antoinette’s Petit Hameau, we miss the last passenger trolley and have no option but to walk for what seems like many miles. We enjoy several pleasant days in Paris before we head to the Loire Valley. Mama wants to see some châteaux.

We take the TGV train to Tours, where we rent a car. Although in 1988, Daddy drove Mama and me swiftly and confidently along Britain’s winding roads, this time he’s happy to yield the wheel to H. Our home base in the Loire Valley will be the picturesque little town of Amboise. The royal Château d’Amboise, a multi-turreted castle worthy of Sleeping Beauty, is the centerpiece of the town. It’s a short, lovely walk to the Château du Clos Lucé, where Leonardo da Vinci, as artist and inventor in residence and buddy to Francois I, spent his final years. The Châteaux of Chenonceau and Azay-le-Rideau are nearby.

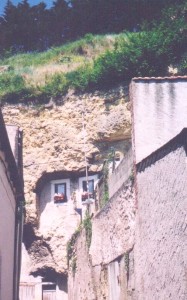

Also within an easy walk from the center of Amboise are several so-called troglodyte homes built into the cliffs of soft tufa, a kind of limestone. The stone, evidence of a prehistoric sea that once covered the area, was quarried for local building. The resulting caves offered unique housing opportunities. Much sought-after, they’re typically equipped with most modern conveniences and need no heat or air conditioning.

From Amboise, we drive west to Rennes. Although it’s familiar territory for my husband, I’ve never been here. As we walk through the old town and the University section, he recalls his student days. I’d heard the stories, now I can experience the setting first-hand. He points out the buildings where his classes met, the cafés, parks and shops he frequented. As he shows me the route he took to school, I can see him riding through town on his moped, blonde curls visible under the helmet. Thankfully, he was wearing that helmet when a truck hit him one morning. Were it not for that helmet, it’s doubtful we’d be standing here together.

Although H had been in sporadic contact with his French host family since he stayed with them in 1988, he hadn’t told them our travel plans. Our time would be short, and a visit could be awkward since my parents speak no French. But on the road to Mont Saint-Michel, H realizes that we’re tracing his old route to town. Their home is so close. Seems like we almost have to drive by. H has no trouble spotting the house. As though on cue, his French parents are walking out the front door. They recognize H immediately, after fourteen years and no prior notice of his arrival. Monsieur and Madame Treguier welcome us warmly. They are merrily insistent that we return for dinner that evening. We find ourselves saying yes. Who knows when we’ll be back? My parents urge us to go. They’re invited, as well, but they’ll stick with dinner at the hotel. That’s probably a good decision, since Daddy tends to find any long conversation tedious, even if it’s in his own language.

That night, after a beautiful day with my parents at Mont Saint-Michel, H and I are treated to what feels like a homecoming meal. The Treguiers’ younger daughter lives in town and is able to join us. Of course she’s a grown woman now, but H remembers her as a little girl. Madame Treguier brings forth dish after delectable dish, seemingly effortlessly from her tiny kitchen, beginning with a dramatically heaping platter of bright red langoustines. I really don’t know how she does it. For H and me, it takes all our collective brain power to speak sustained, passable French for several hours. The constantly flowing wine helps, until it hinders, and we have to resort to covering our glasses with our hands. The Treguiers are as generous with their wine as H had remembered. In fact, as soon as we arrived, Monsieur Treguier had proudly showed us his brand new wine storage area, his “cave,” built under the garage.

It’s a wonderful, celebratory evening. I get to peel back the layers of my husband’s life, just as I have my own. I see him as his host family remembers, as a very green, very American college boy. They recall fondly that when he first arrived, they secretly despaired. Would they ever be able to communicate with him? He had had only one year of college French, and his language skills were rudimentary. Fortunately, he showed remarkably swift improvement, and his charm was immune to the language barrier. Wow, I thought. With many more years of French study behind me, I’d lacked the courage to stay in a French household during my Paris summer.

Seeing H through the eyes of the Treguier family brings to light one of the traits I most admire about him: his quiet confidence. Whatever the challenge, if he considers it worthwhile, he’s up for it. Immerse himself in a totally French-speaking environment with minimal skills? He’ll manage it. Drive an enormous delivery truck through all the boroughs of New York City? Sure. Fix the car, any car? Easy. Repair the hole in the ceiling? Yes. Master windsurfing on his own? He’s done it. Teach his daughter to ski? Of course. Show her a better approach to that algebra problem? Certainly. Yet he’s never showy or arrogant. He has no ancestral château, but what a guy. Indeed, what a great guy. I can tell that the Treguiers agree.

That night in Rennes, the Treguiers’ deep affection for my husband is apparent. What’s more, they extend their high regard and good will graciously to me, and even to our daughter, back at home. They urge us to return in the near future, to bring her and spend more time with them. As we say our goodbyes, it’s like leaving a family reunion in some best of all possible worlds. It’s one of those times when the bonds of true friendship are revealed at their strong, resilient best, stretching across miles, years, languages and cultures.