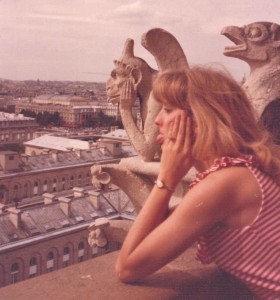

As I’ve mentioned, I was lucky to receive an early formative introduction to France, its language and culture, thanks to a remarkably dedicated middle school teacher. See Vacation ’75: Part I: Paris, March 2013. Mrs. Correll emphasized the value of college study abroad, and I took her at her word. The summer after my junior year at UGA, I headed to Paris. Courses were held in the hallowed halls of the Sorbonne, where Mrs. Correll had received her Master’s degree. We had the option of living with a Parisian family, but I found the prospect of total immersion in French too daunting. My residence that summer was a dormitory at the Cité Universitaire, a complex for visiting international students.

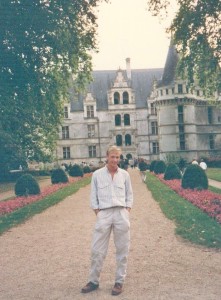

My husband came to love France during his undergrad years at Union College in Schenectady, New York, a small liberal arts college that aims to turn out well-rounded students. Scientists as well as artists are encouraged to spend time in foreign study. H majored in mechanical and aerospace engineering, but he also studied French. He lived with a French family during a semester in Rennes, and before the program began, he and a buddy meandered through Europe by train. I distinctly remember telling a friend about H soon after we’d met as grad students, “He’s an engineer, but he speaks French!” My friend agreed that this was quite unusual. Maybe things have changed, but in the early 90s, the typical Princeton Ph.D. who toiled in the labs of the E-Quad did not speak French, unless it happened to be a native language.

As I look back, I see that our mutual interest in French was a primary factor in bringing my husband and me together. Now, after nearly nineteen years of marriage, we share so much: a home, a church, fundamental values, a daughter, family, friends, a dog and a turtle. But we began as two strangers with very little in common. When we met at that grad college barbeque, he was just beginning his engineering courses at Princeton and his research into “the thermal decomposition of nitrous oxide.” I was writing my dissertation on medieval illuminated manuscripts, having finished my coursework and research abroad. My funding had run out, and I was working as a professor’s assistant in Intro to Modern Art. Our interests, on the surface, could hardly have been more different. And then there was the age difference. He was a dewy twenty-two. I was about to turn twenty-nine. Those seven years appeared to stretch like an unbridgeable river. No betting person would have put money on our going on a second date. Maybe not even a first.

But there was that French connection. We couldn’t discuss manuscript illumination or the burning of nitrous oxide for very long, that’s for sure. But we could talk for hours about France and our experiences there. Did that French link make him think twice about me? Consider that I might not be a hopelessly artsy, aging pseudo-bohemian? Was it the point that convinced me of his unexpected depth, of some wisdom beyond his years?

French was, and still is, a fertile area of common ground between my husband and me. While neither of us makes any claim of fluency or expertise, our appreciation for the country and the language is genuine and heartfelt. We don’t sit around and speak French and think how sophisticated we are, or how cool we sound. We know we don’t sound particularly cool. But we find humor in what we consider the quirks and oddities of the French language. For example, to our American-trained ears, the word pneu (tire), sounds silly. And we find it amusing that a stick to stir coffee is called, rather formidably, “un agitateur.” But then we reconsider and agree that the word is decisive and definitive, unlike our American terms. (Is it coffee stir, or coffee stirrer, or stir stick? I really don’t know.) The French seem to have a specific word for everything, and we respect and admire them for that.

Our mishaps in speaking are a source of many laughs. A favorite story is from H’s student days in Rennes. He’d bought a little second-hand moped to take him from his family’s house into the center of the city. One night after late partying he locked it up near the university and got a ride back with friends. The next day it was gone. He reported the missing moped to the police, saying “Quelqu’un a violé ma mobilette.” He was asked to repeat his story to officer after officer, each of whom maintained a strenuously serious expression. H was pleased that his report was being received with impressive gravity, certain that swift action would be taken to retrieve his trusty vehicle. Only later did he realize he’d been saying that his moped had been violated, rather than stolen (volé).

H and I first traveled to France together in the spring of 2002, with my parents. They had funded most of my several visits but had never set foot in France themselves. We thought about taking our daughter along. She wasn’t yet three. We didn’t consider it very long, since H’s parents were willing to take care of her. We’d wait until she was old enough to appreciate the wonder of being in a foreign country.

Then, as they tend to do, the years zipped by with lightning speed. We realized we were in danger of waiting too long for our family trip to France. Our daughter’s idea of the perfect holiday is no longer hanging around with her parents, even if it does happen to be in an exotic locale. And before long, she would be a young woman in college, no longer our captive child.

This past spring break, the three of us flew to Paris.