Now that the question of dog or no dog had been settled in the affirmative, my husband asked for only one consideration: a dog without excessive fluff.

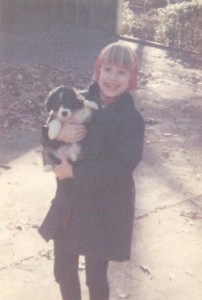

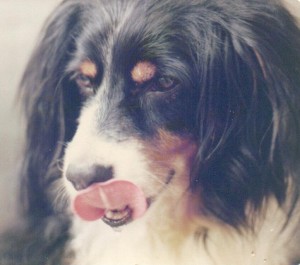

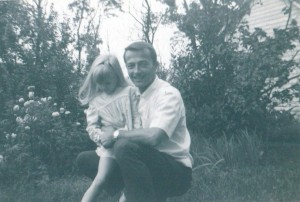

At first this saddened and irritated me, because I love the fluff. While there are many short-haired, sleekly handsome dogs, my personal tactile preference is for thick, luxurious fur into which I can sink my face and fingers. I had envisioned a cuddly mixed breed puppy, perhaps with Chow Chow, American Eskimo Dog or Keeshond parentage. Or maybe we could find a black and white Popi look-a-like. (His full name had been Potpourri, to reflect his mixed heritage of Chow and Cocker Spaniel.) But when it hit me that I would be an adult instead of the child in this dog-human relationship, I began to see the housekeeping advantage of less fluff. I would be the primary wielder of vacuum, Swiffer and dust-cloth. Still, I needed a dog with substantial fur.

Early on in our dog-decision process, I assumed we’d simply look for an appealing mutt at the Humane Society, likely the best place to discover a potential Popi II. But as I considered my childhood dog’s personality in a less nostalgia-tinged light, I began to second guess both the shelter and the Popi aspects of the plan. My beloved dog’s loyal devotion to my parents and me was a big plus. We were all the pack he needed. He had little interest in other humans or in his fellow dogs. He didn’t require doggie play-dates (an unheard-of concept then). We saw him as highly intelligent, discerning, unwilling to waste affection on strangers. These positive points had their corresponding negatives. Popi didn’t suffer fools; he didn’t take crap from anyone. On a number of occasions, when provoked, he bit people, usually children. He wasn’t vicious; he never bit without due cause, and he rarely broke the skin. During those less litigious times, such behavior was more frequently seen as justified. Parents now tend to think a dog has no business biting their child, even if the kid does sneak up and roughly wrap a belt around the dog’s neck or try to stuff the dog into a box. I realized that while I still appreciated Popi’s aloofness, I didn’t want to deal with a biting dog, no matter how justified.

Another problem with choosing a shelter dog is our family’s soft-heartedness for animals. What if we saw a dog that tugged at our heart strings but somehow wasn’t suitable? I was afraid we’d be haunted by the memory. I still remember a dog that looked plaintively at me twenty years ago when I happened to walk past it at an adoption event at a shopping center. I was a student; I had no permanent address; I couldn’t get a dog. But I can’t forget that face begging for love. D and H are similarly inclined.

Gradually, I realized we should consider a purebred dog. I had been a lifelong champion of mutts, so this took some getting used to. With a purebred we could avoid the problems of uncertain temperament that can result from a mixed breed’s unknown parentage. The best path, we concluded, was to decide on a breed that fit our needs, then locate a reputable breeder. We would be more likely to get a non-aggressive dog. We would have a higher chance of getting a puppy. And we could better avoid the heartache of having to refuse a dog that wasn’t a good fit.

It took us a while to settle on a breed. Most were too large or too small, too clumsy or too yippy, too shaggy or too sleek, too friendly or not friendly enough. My daughter and I were watching the Westminster Dog Show when we spotted an unfamiliar breed, the Shiba Inu, of Japanese origin, a smaller relative of the Akita. This fox-like dog has a jaunty walk, proud bearing, pointed ears, bright slanting eyes, a tail curled to resemble a bagel, and red velvety fur that is thick but decidedly not fluffy. D and I were entranced. We felt sure we’d hit upon a dog that even H could love, or at least abide, especially when the announcer referred to the Shiba as very neat, clean and intelligent, “a big dog in a small dog’s body.”

The more I learned about the breed, the better it sounded. The Shiba tends to be reserved around other dogs, but not aggressive toward people. Maybe we could get a touch of Popi’s aloofness but none of his bitey-ness. D and I were excited; we could sense our dog dream becoming a reality.