Two weeks ago today, my friend Doug passed away. Doug had a zest for life that never flagged, despite the direness of the situation. He was a character. He was great company. He will be sorely missed.

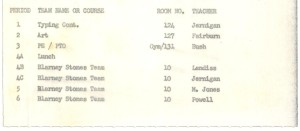

Doug was known for his sharp memory, keen sense of humor, and flair for observing the odd detail, qualities that made him a compelling storyteller. He had copious amounts of material to draw on, including high school days in his native Seattle, where one of his classmates was Jimi Hendrix.

Doug had an exceptional ability to talk to anyone about anything. What’s more, he could make the exchange interesting. Early in his career he worked for the CDC in the effort to combat the spread of syphilis. He coached interviewers on effective methods for talking with syphilis patients about those to whom they may have spread the disease. If anyone could make a conversation about VD less uncomfortable, perhaps even verging on enjoyable, it was Doug. Not simply a skilled talker, Doug was a thoughtful listener and an engaging conversationalist. He delighted in the give and take of a spirited conversation. He would have been in his element with Samuel Johnson in the clubs and coffeehouses of eighteenth-century London, or with the circle of the recently deceased Christopher Hitchens.

Doug found his true calling in his career with the Fulton County Public Defender. His outlook made him uniquely suited to the position. He had a profound respect for all people. He empathized especially with underdogs and with those who had been dealt life’s poor hand. Doug took pleasure in getting to know his clients. He could see their admirable qualities despite the shadows of their terrible decisions and ill-advised deeds.

Doug was a dapper dresser with a discerning eye. For years, he and my father made an outing of the annual sale at Muse’s, the old Atlanta menswear store. Doug recognized style wherever it appeared. I remember his remarking on the classic élan of one of his clients who happened to be a transvestite. He was so impressed with her smartly tailored dress and lovely jewelry that, with a thought to his wife’s upcoming birthday, he asked for shopping references.

For the past two decades, Doug had suffered from syringomyelia, a rare degenerative neuromuscular disease. It began with a disturbing loss of balance first noticed during his neighborhood jogs. Over the years, it progressed at varying rates, leading toward a nearly complete loss of physical mobility and bringing with it a host of related issues. As the disease accelerated, Doug never lost his dignity or his ability to laugh. When he could no longer work, his computer and the Internet served as lifelines to keep him mentally active and in touch with his many friends and acquaintances. He continued to be a force in the legal community, appearing remotely on several occasions as a commentator on Court TV.

During our visits to Atlanta, my daughter and I liked to stop in to see Doug on our walks to the park. He and I discussed recent events and swapped memories of former neighbors. Doug was a great resource for entertainment trivia, and he never forgot names. He knew, for example, that Rashida Jones, who had just begun appearing on The Office, was the daughter of Quincy Jones and Peggy Lipton. Doug and I liked similarly offbeat movies and TV shows. I regret that I never got the chance to ask him if he watched Justified. Its dark, ironic humor would have appealed to him, I think. And in its colorful, flawed characters, he may have seen glimpses of his former clients.

When my daughter was very young, her primary motivation for stopping by Doug’s house (other than to marvel at his futuristic wheelchair) was the chance to see the elusive and fabulously fluffy Elvis the cat. Elvis is shy and typically avoids children. If we stayed long enough, though, he would usually appear from beneath the sofa, or slink in furtively from another room. After staring intently for a while, he sometimes allowed my daughter to pet him. Doug told D it was because she behaved in a calm and grown-up manner that Elvis was willing to trust her. But he didn’t condescend to children, and D came to enjoy talking with him as much as I did. She appreciated his addressing her as a full-fledged person, even when she was a preschooler. Doug asked interesting questions, and he heard her responses. He avoided the painful clichés children must often endure from well-meaning adults.

Doug’s devoted family was his greatest treasure. He never bragged, but he adored sharing amusing anecdotes about his beautiful wife and daughter, his handsome son. He chose Christmas and birthday gifts for his wife with the utmost care. To preserve the surprise, he had her presents sent to my parents’ house, where my mother would wrap them. Sometimes, however, his gifts needed no festive paper. As his illness increasingly confined him, he treated his wife to unusual thrills with an emphasis on motion: a flight in a hot air balloon, a ride in a speeding racecar. Doug was a NASCAR devotee. Anyone who thinks all NASCAR fans are cut from the same cloth never met Doug. His elegant wife is an even less likely fan, but under the influence of his enthusiasm, she became a convert.

After so much of his life spent in hospitals, subjected to a dizzying array of treatments and procedures, Doug took his last breath at home, asleep in his own bed. I like to think that where he is now, the opportunities for fascinating conversation are even more abundant. And he has no need, anymore, for that cool wheelchair.