The worst part of the drive from the airport is now over, and Daddy is beginning to slow down. We’re in my old neighborhood, and I’m trying to soak it all in, trying not to miss any detail. Some houses remain unchanged for the last two decades, still in need of loving care. Others are in the course of being popped up to three times their size. Some invite repeated renovation; each year sees a new style, wing, or entry. Others have disappeared completely, and I try to remember what used to be on each bare muddy lot marked only by a Porta-Potty. Ever since General Sherman burned Atlanta in his March to the Sea, the city’s state of flux has been fast-paced.

My parent’s house, though, looks very nearly the same as it did when I was last here this summer. It remains essentially unchanged since 1929, when it was built, in a leafy in-town neighborhood of small brick Tudors and Norman cottages. We moved there in the late 1960s, after two years in a suburban rental. Our new house was a mess, but it immediately felt like home. My parents spent years uncovering its classic features–hardwood floors hidden under gold-flecked linoleum and lavender sculpted carpets, plaster walls concealed by wood-grained wallpaper. We gradually updated the kitchen, which still contained its original appliances, chrome-edged, simulated stone Formica countertops and metal cabinets. But we made no structural changes or additions. My mother’s interest in redecoration has not dimmed, but the alterations are smaller in scope now. My childhood room is just as it was when I moved away: the same wallpaper, the antique cherry furniture inherited from my father’s aunt.

I know every quirky feature of the house by heart: the sharply curving narrow driveway littered in the fall with acorns, the sound of the brass knocker rattling as the heavy front door closes, every creak along the center hall, the loud click of the light switch in the stair hall, the bathroom faucet handles that rotate the wrong way, the back hall steps lined with walking shoes and cartons of Coca-Cola, the old ping-pong table in the basement used for storage and craft projects, the view of the back yard from my old bedroom window, and the unique, inimitable smell of home.

It’s somewhat unsettling to be here without my daughter. I keep thinking she’s upstairs in the playroom, which has become a sort of toy museum. She’s probably unpacking the boxes of baby dolls, stuffed animals and Barbies that my mother lovingly maintains. Or maybe she’s setting up a tea party at the little pink table in the alcove, or rearranging the furniture in the doll house. But the table, the doll house and my girl are all at our home in Virginia. And if my daughter were here, the toys wouldn’t capture her attention nearly as much as my old Seventeen magazines and the wardrobe bags full of vintage clothes in the attic. (My mother has a great gift for design and sewing, and for many years she was possessed of a phenomenal energy that led her to make more clothes than we could ever wear).

It’s disorienting, as well, that there is no dog here. If I happen to see a shadow out of the corner of my eye, I think it’s the dog. And each time we leave, I look around instinctively to hug him goodbye. But I’m not sure which dog I expect. Is it my childhood dog, who has now been dead nearly twice as long as he lived? I often think I hear him, my sweet Popi, my stand-in for a sibling. He was a black and white cocker spaniel and chow mix, as aloof to other dogs and non-family members as Kiko is friendly. He often nudged open a partially closed door with his nose, a sound I hear repeatedly in my mind. Popi was so comforting when I was upset—he’d put his muzzle on my knee and look into my eyes with such compassion. Or is it my funny Kiko that I think I hear or see? But Kiko has never set one neat little paw in this house.

Returning to a childhood home is a bittersweet pleasure. The things of the past get confusingly jumbled up with those of the present. Old memories collide strangely with current reality. My brain is stretched in uncomfortable ways, and I feel young and old, happy and sad, at the same time. I guess it’s a good thing I don’t often go back alone to my old home.

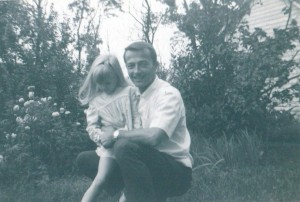

Popi, as a puppy, and me. It was his first Christmas, and our first in the new house. Of course Mama made my dress and vest, and my daughter wore them, as well.

Popi with next-door dogs Felix and Cocoa, outside our back door.

He didn’t like them, but he tolerated them occasionally.

Popi, not long before he died, at age 15.