My dog Kiko turns fourteen this summer. His face is now mostly white, but otherwise his appearance has barely changed since he reached adulthood. He’s as lean and trim as always, and because of his small size relative to the Labs and Doodles prevalent in our neighborhood, he’s still occasionally mistaken for a puppy. But recently he’s begun to show his age. When descending the stairs, his back legs move stiffly, as though tied together with an invisible cord. On walks, he’s considerably slower, especially on the way home. Walking with our usual pack means little these days, because we’re quickly out of step and far behind. Kiko has always set his own pace, paying scant attention to the fellow canines he sees regularly. He’s a very social animal in that he wants to greet every new dog he meets (or even glimpses at a far distance) but after that initial encounter, he’s off on his own. For many years he typically led our pack, despite frequent stops for extensive sniffing, but now, more frequently than not, he dawdles and dithers. He rambles, he meanders, he doubles back, then stops absolutely, as though gripped by indecision. And once home, he spends the greater part of the day in a sound sleep.

Kiko’s hearing seems to be less keen. Has his sense of smell become more acute, to make up for the other loss? Sometimes he appears overcome by the sheer volume and variety of aromas he’s attempting to untangle. He has always preferred smells to the actual dogs or humans associated with them, but now the preference is more pronounced. I’ve heard that as long as a dog can smell, a dog enjoys life. According to this measure, Kiko is enjoying life immensely. I find this thought comforting.

Usually now, Kiko and I head out alone. We’re a pack of two, just as we were during his puppyhood, before I had a number of friends with dogs. We tend to walk early, soon after sun up. We go then because the day is at its loveliest, and because it leaves me the option of joining my friends later. If it’s socializing or exercise I want, it’s best to leave Kiko behind. Of course, he doesn’t like this. If he’s home, he wants me there, particularly after all the togetherness we’ve shared during the last pandemic year. After we return from a walk, he eyes me suspiciously, like a jealous boyfriend. I pretend to settle in at the computer, and soon he hops up into his bed. I sneak out quietly if I go.

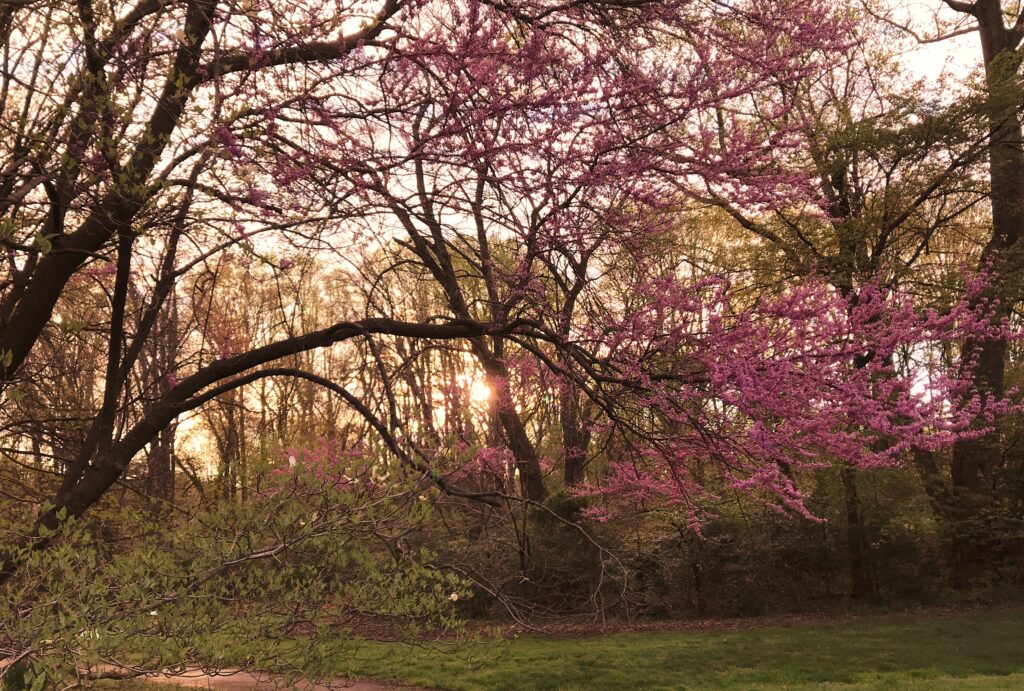

I’ve come to appreciate walking alone with Kiko in the early mornings, though. There is little to divert my attention from the pervasive beauty around us. I’m attuned to the springtime world, which often glows in a rosy, golden light, especially when filtered through deep pink cherry blossoms and tangerine-hued maple buds. The birds are at their most active and celebratory. Kiko lingers, his nose at the base of a clump of daffodil foliage, takes a few hesitant steps, then pauses again, and again. There is no point in rushing him. I summon patience, and breathe in the sights and sounds of the sparkling new April day. If I surrender to the moment, and release the urge to speed things up, I can sense the natural world regenerating and rejoicing. I can be part of all this daily morning glory, because my odd, old dog brought me to it. Together, we’re fellow creatures basking in “God’s recreation of the new day.” The words and melody of Morning Has Broken* seem to float in the sweet-smelling air:

Blackbird has spoken like the first bird.

Praise for the singing, praise for the morning!

Praise for them springing fresh from the Word!

Sweet the rain’s new fall, sunlit from Heaven,

Like the first dewfall on the first grass.

Praise for the sweetness of the wet garden,

Sprung in completeness where His feet pass.

Mine is the sunlight, mine is the morning;

Born of the one light Eden saw play!

Praise with elation, praise every morning,

God’s recreation of the new day!

*While Cat Stevens made this song famous, the words were written by Eleanor Farjeon in 1931, inspired by this verse of scripture from Lamentations 3:22-23: “The faithful love of the Lord never ends! His mercies begin afresh each morning.” The tune is a traditional Scottish Gaelic one called “Bunessan.”