My earliest church memory may be of Vacation Bible School. It’s a vague, but agreeable recollection: I’m about three years old, sitting with several other children in miniature wooden Sunday School chairs. A sweet-faced elderly lady tells Bible stories. We have juice and cookies. There’s an old piano, and we learn the Zaccheus song: Jesus said, Zaccheus you come down, for I’m going to your house today. We finish with “Jesus Loves Me.” As I recall, I was content to be there in the little stone Methodist church in the Kentucky town where my grandparents lived.

Back then, it was just Bible School, not yet routinely prefaced by “Vacation,” not yet shortened to VBS. It wasn’t slickly packaged or corporate. But the essential message, then and now, is the same: Jesus does, indeed love you.

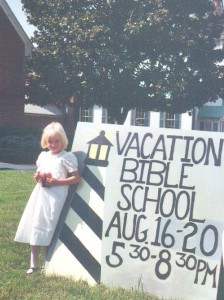

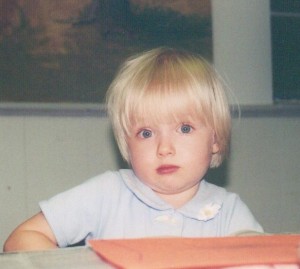

This is a message I wanted my daughter to hear from others besides me and her immediate family. I wanted Vacation Bible School to be woven into the fabric of her early life, just as it had been for me. She first attended when she was two and a half. We had found our church home, and she would be starting preschool there in the fall. VBS was her first taste of being away from me, in a group of her peers, for a short time.

My daughter and I have both come a long way since then. D, of course, has grown from toddler to teen, from plump baby to willowy young woman. During her initial VBS, she was a somewhat reluctant participant in the preschool group, one who would rather not leave her Mama. Now she and her friends lead Bible Adventures. As for me, back then I helped lead Crafts, and I was youngish. Now, as the mother of a high schooler, I’m closing in on oldish. I have, however, become somewhat wiser. I’ve learned a few things from all my years of VBS.

First, I learned that I don’t like leading Crafts. It took me two years to realize that this was not my niche. One night I was standing by, trying to assist, as a child locked a bottle of white school glue in a death grip. Glue puddled on the construction paper, on the table, on the boy’s hands. Still he kept squeezing, resisting my helpful advice: That’s enough glue! Once the bottle was nearly empty, and as though in utter surprise, he began to wail, “Too much glue!” Yeah. No kidding.

I hate leading crafts, I thought. I hate the excesses of glue and glitter. I hate trying to organize the multi-piece, pre-cut foam assemblages, each small segment (moon-faced child, smiling sun) individually wrapped in cellophane. Certain pieces tended to vanish, causing great distress among the kids: I need a red bird! Where’s my purple dress? Did you take it? The Crafts experience, under my leadership, didn’t seem to be furthering the “Jesus loves you” message. At the end of each sticky, messy, frustrating evening, I wanted to run away and never return. I wanted to be far from any church, far from all children, far from everyone.

But on the final night, I remembered why we were there. H and I got to see our tiny girl standing at the front of the sanctuary with all the other children, singing the songs they learned during the week. Even before I became a mother, I’ve been a sucker for kids singing in church. Watching our daughter participating with the group made it magical. She looked like an angel. It was for moments like this that I had always wanted to be a parent.

Then a minor tragedy occurred. In Crafts (and under my purview), the kids had made shakers for use during the final musical program. We had filled paper plates with small pieces of gravel and stapled them together. D was brandishing her shaker enthusiastically when a staple or two gave way. Chunks of gravel and a cloud of dust exploded all over the choir loft. D burst into tears and bolted, screaming, searching frantically for me in the pews.

Another thing I learned that year was this: don’t use gravel to make shakers. The instructions in the Crafts leader guide need not (and should not, in certain cases), be followed to the letter. I would give this advice to a future Crafts leader. Next year, I would find a better fit, and I would go on to learn more important lessons.