I have a friend whose vocation–one of her true callings–is searching out the best deals in thrift stores. She’s motivated not by monetary gain, but by the thrill of the hunt. Occasionally she’ll sell some of her finds on eBay. But more often, she makes gifts of them to those who will most appreciate them. She’s one of those people who can, and does, talk to anyone she meets. And she meets many people. She was in our dog-walking group for the ten years that her family lived in our area. As soon as a new family moved to the neighborhood, she could tell us their names, their background, and several interesting anecdotes about them. Wherever she is, whether on walks with sweet Cali, her big, shaggy golden doodle, or in her favorite thrift stores, she’s immersed in community. At a local church-run shop, she was one of the Tuesday regulars, those who line up early for first dibs at newly displayed merchandise that arrives over the weekend. There she met a diverse group of friends, and it became part of her mission to assist in their searches. Quality wool sweaters in fall colors for Esther’s twin grandsons in Roanoke? Office attire in Size 5 for Maria’s young adult daughter in the Philippines? Just-so serving pieces for Sofia’s niece’s at-home wedding reception in Manassas? Found, found, and found, in each case, with several options.

My friend was well aware of my dollhouse hobby. She had been on the lookout for a while, at my behest, for a miniature house that could benefit from a thorough renovation. The plainer, the better. When she spotted one on a Tuesday morning at her favorite thrift shop, she quickly texted a photo.

Yes! I’ll be right over! It was the ideal blank dollhouse canvas I’d been wanting. It’s hard to imagine a more basic structure. It was sizable, but it fit, just barely, in the front seat of my little car.

For the re-do, I envisioned a stately Greek revival house in gray and white. My husband measured and cut (two things I don’t do well) a triangular pediment for me from a thin sheet of plywood. I removed the few remaining shutters and painted smaller pediments over each window. I added a central Palladian window, and Corinthian columns on tall bases. I painted the steps, chimney, and foundation level to resemble stone. I added pots of flowers and topiaries, and a couple of flowering trees on each side. I kept the florals to a subdued palette of green, white and yellow. Only the front door remains unchanged.

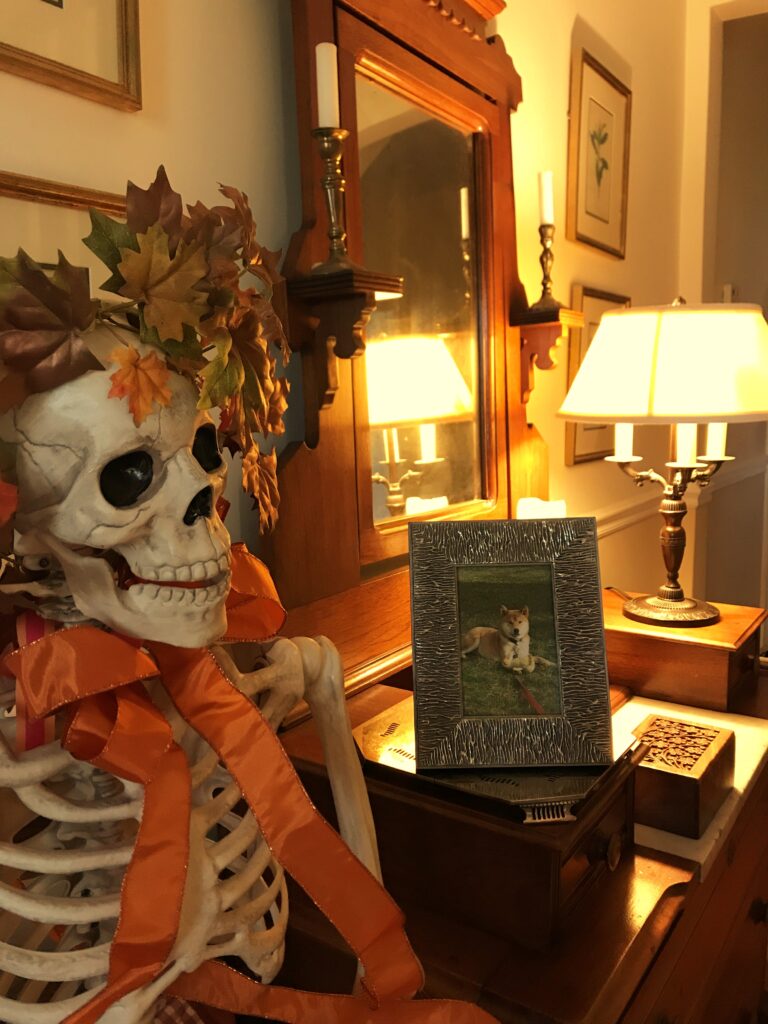

Ever since deciding on the color scheme, I knew that the exterior would feature cats. Most of my houses are adorned with dogs and/or foxes, along with a few birds, squirrels and chipmunks. When my dog Kiko died, I added him to the Red Panda house I was finishing. This house, I’d decided, would be a sort of memorial for my favorite Atlanta feline. Streak, all fluffy gray and white elegance, was my idea of the absolutely perfect cat. I began seeing him when, living at home between undergrad and grad school in the mid-80s, I passed his house on daily neighborhood walks. With very un-catlike behavior, Streak would run out enthusiastically at my approach. If I didn’t see him immediately, I’d call for him, and he’d appear. He’d greet me with a loud, decidedly welcoming meow. I’d spend some time admiring him before resuming my walk. He’d purr and circle my legs. I’m allergic to cats, but a few moments outdoors with a cat don’t bother me. And a few moments with a living, breathing masterpiece like Streak–those to me were priceless.

Just look at that lion-like ruff, those symmetrically striped, magnificently furry front legs and paws, those yellow eyes, pink nose, delicate ears, and intense, intelligent gaze. All these decades later, and I’ve never met a cat that was Streak’s equal in looks or personality.

If not for my friend, the thrift store guru, I might not have had the pleasure of creating a tribute to Streak. None of my painted cats does justice to the one that inspired them, but I enjoyed the attempt. Streak will forever feature in my favorite Atlanta memories. Now, in the child-like part of my brain that still imagines my painted houses as sanctuaries for cherished companions, I can envision him living here. He’s waiting by the front door to greet me. Content and cozy with his dear cat family, Streak is nearby in all his feline fabulousness.