Last year I wrote about how H’s sister and her husband brought their new baby, then three months old, to Cape Cod (see Our Summer Village on the Cape, September 2012). I marveled at their bravery in attempting a vacation at this stage of their child’s life. H and I found it too stressful to venture far from home during our daughter’s first two years. Last August, D’s new cousin was a cuddly, portable bundle. He needed everything done for him, but he lacked the power of locomotion. He stayed where he was placed. I wondered what even greater reserves of parental courage and vigilance would be required a year later, when their son would be a new walker.

Our nephew, at thirteen months, in May.

In August, he rarely paused long enough to be photographed.

This past summer, our nephew took his walking very seriously indeed. He was constantly on the move, always working on his form. The shifting sand and the piles of dried seaweed threw him for a loop. He soldiered on, carefully and deliberately, but he made it clear that he wasn’t about to go it alone. At the least hint of unsteadiness, he thrust out a hand and emitted an impatient squawk, his way of demanding that Mama or Daddy hasten to his side. He would accept help from Grandma and Grandpa, but remained wary of H, D and me. We hadn’t yet put in enough hours to earn his trust, and I could respect him for that. He was equally quick to indicate when assistance was unwelcome. The worst offense was to pick him up without permission. This was grounds for loud and vigorous protest.

When the baby was happy, he was very happy. He smiled, giggled, clapped his hands gently and soundlessly, and, when asked, performed his signature move, the subtlest of stationary dances, a barely perceptible, and very funny, shifting of his hips. When he was touchy, he was very touchy. Often his fiery irritability had no explanation. Luckily for him, whether glad or mad, he was awfully cute, a sweet-faced, doll-sized figure in a floppy sun hat and long shorts.

Considering that D’s cousin negotiated the beach with the utmost care, I was at first surprised to see that hard surfaces inspired in him a devil-may-care attitude. Once his little foot touched a sidewalk or a gravelly parking lot, if given the chance, he was likely to break into a wild run. He looked like a tiny fugitive attempting a last-ditch effort at freedom. These feats of daring frequently ended badly, in tumbles, scrapes and anguished screams.

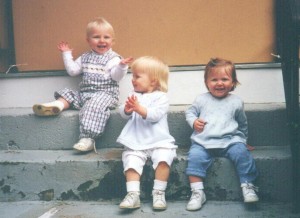

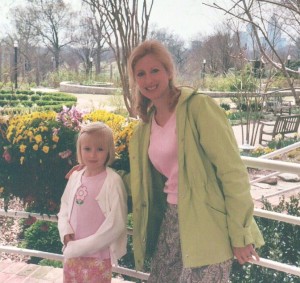

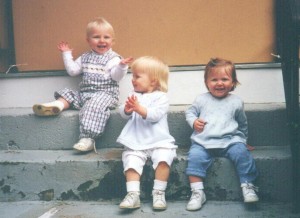

Then it began to come back to me: our daughter behaved similarly when she was about his age. On soft, unthreatening grass, she walked with unhurried ease. But should she discover a patch of rocky, ill-paved concrete, that’s when she’d tear off in a desperate sprint. She was careful under relatively safe circumstances, yet often reckless when there was a hint of danger. When I hosted the baby playgroup for an Easter egg hunt at our new home, I looked forward to seeing the children roaming happily on the big front lawn. But D and her friends couldn’t care less about the nice grass or the colorful eggs hidden there. It seemed they had decided unanimously that the only game in town was scrambling up and down the rough concrete stairs off the back porch. Up and down, over and over, while we mothers hovered anxiously, trying to focus their attention elsewhere, to no avail.

During D’s toddler years I often lamented her frequent instances of contrariness. If I really wanted her to do a certain thing, she was likely to put all her effort into doing the opposite thing. It seemed like God’s joke on parents. Of course, he knows how we feel. In that paradise garden he lovingly created for us, there were boundless delicacies and only a single prohibition. We know how that went.

D and friends, at about sixteen months old, on April 14, 2000. Safety concerns led my husband to block off the top of the stairs with a plywood board; we entered the porch via a ramp installed by the previous owner. The playgroup still insisted on climbing up and down these ugly stairs to nowhere. The steps, along with our old porch, are long gone.

Last year at the Cape I could envision D and her new cousin, some day, hand in hand, an adorable sight as they headed down to the bay. I had hoped it would happen this summer, but that was premature. Our nephew wasn’t ready to go exploring without his parents at arm’s reach (except when he was racing across the pavement). I had almost forgotten children’s insistence on their own schedules, their own agendas. They won’t be rushed, and they have their own distinct personalities, no matter how young.

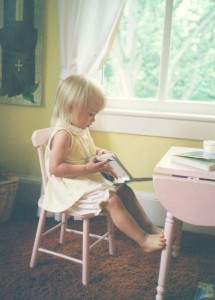

Looking back on the early years with our daughter, I see that I wanted her to be a small, improved copy of me, with all my likes and dislikes, yet lacking my faults and weaknesses. There were times when I had counted on a different developmental pace for D. I remember reading to her when she was in her second year. I expected her to soak up enthusiastically the nuances of plot and illustration I pointed out to her, but she wasn’t impressed with such details. She just wanted to get on with it, and she demanded insistently: Turn page! Turn page! If I didn’t do so, she would grab the page roughly and turn it herself. The majority of her picture books from this era are ripped and fragmentary. When D wasn’t quite three, we spent a weekend in Princeton, and I had visions of her eyes widening at the beauty and elegance of the collegiate Gothic architecture. But she rarely looked up; all she wanted to do was draw in the dirt with a stick. My husband recognized the absurdity of my expectations, but he had his own. He was disappointed when his daughter showed no interest in advanced math or engineering concepts at two and a half.

D in June 2000, at eighteen months, free to turn these unrippable cardboard pages at her own pace.

Watching my sister- and brother-in-law cope with the toddler stage of their son’s life, I remember how H and I, too, had to learn when to lend our daughter a hand, and when to let her go. Sometimes we had to let her run, even if it was across hard pavement. As her little cousin roves farther and faster on his own two little feet, our daughter ventures farther and more frequently from us, her parents. This year on the Cape, she was among the crowd of teenagers that wanders the grounds of our cottage complex. She rode the bus into Ptown with her friends. She stayed out later than ever at night with the group, talking and laughing on the green. Her irritability, like that of her baby cousin, may be fierce, sudden, and without explanation. Now, with school and all its related activities under way, H and I might define our primary parental obligation as that of the chauffeur. Certainly, we seem to be most appreciated when we complete our driving duties efficiently, silently, and disappear immediately afterwards. But like her cousin, our daughter continues to learn to walk her own walk, to do her own dance. She still needs us looking on, if not holding her hand. We’ll have to relearn old steps as we try out new ones together.

Next year at the Cape, our nephew will no longer be the baby. He’ll be a big brother to his eight-month old sibling, expected next month. Other dim memories of our daughter’s babyhood will be refreshed as we watch our fifteen-year old helping her two young cousins pursue their unique choreography. And, of course, creating some of her own original steps.

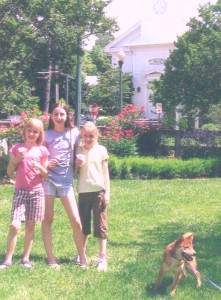

D, age fourteen, at the Cape, in August.