Can we bring home the tree without first decorating the dog?

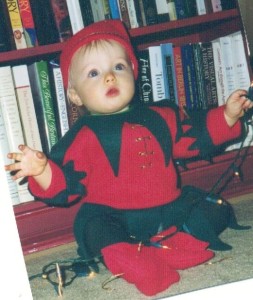

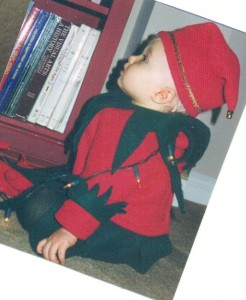

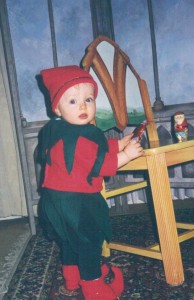

In years past, ideas for Christmas-themed posts flowed from me in abundance. I love the season, and I found so much to write about. This year, the fountain dried up. Seemed I’d exhausted all possibilities. I’d written about the annual ornament-making marathons Mama and I undertook during my childhood, about how my daughter and I continued the tradition. Wrote about my long-lived gingerbread village, the little lights, the decorative oddities (that Devil Doll). Wrote about why we chose such ugly Christmas trees when I was very young. Wrote about decorating the dog, the tree stump. What else was there to say?

I thought inspiration would hit me as we decorated the house, a process that begins during the week of Thanksgiving. The idea is that we get everything looking beautiful and will then have a chance to enjoy it: the house aglow in the winter night, the festive greenery, red berries, all the reassuringly familiar trappings that make the season special. It shouldn’t be a bad thing to get an early start on Christmas. We do it in church, after all. Our “Hanging of the Greens” takes place on the fourth Sunday before Christmas. It begins the Advent season of the church year, when we are to prepare for the coming of Christ. While it’s a time to remember and honor Jesus’s historical birth, Christians are also to prepare for the ever-present possibility that He will come again in final glory.

But at our house, decorating early also means decorating longer, and it encourages excess. The five small artificial trees are up by early December. At mid-month, we buy our tall live tree. The table-top living room tree is moved into the family room. Work then begins on the new tree. Decorating it takes several days. We have many ornaments, and my daughter and I are sentimentally and/or compulsively attached to every single one, even those falling to pieces or unattractive. Those will go toward the back. We tend to make only minimal changes in our overall decorating scheme from year to year, because the atmosphere wouldn’t be as cozily homey if we did. That means there’s very little that’s worthy of comment.

This year, more than most, it seemed to me that in our preoccupation with readying our home ready for Christmas, we were getting off-track, missing the point completely. Are we preparing the house but neglecting our souls? That true light of Christ on earth, the light that shines in the darkness–is it at risk of suffocation with all the bright shiny synthetic stuff we heap around it? If Jesus were to appear today, would he cast an appreciative glance at our trio of alpine trees, or comment approvingly on our decision to use colored lights, instead of white, in the playroom? Would he be touched by our thoughtful arrangement of handmade mice around a sleigh full of miniature wrapped packages? Would he say, Well done, good and faithful servants! These beautifully stitched and whimsically arranged Christmas mice are a worthy commemoration of my birth! You have prepared well, and now I am here to take you home. I doubt it.

I also doubt He’d condemn us solely for going overboard on our decorating. The Jesus I’ve come to know has no interest in turning us into puritanical, humorless scolds. (Recall how hard he was on those self-righteous Pharisees.) He knows we’re fairly dim creatures who tend to lose their way. He remembers how his closest friends needed repeated explanations and still never quite understood. He’s patient with our foolishness. But we can’t fool him. He’s knows when we’re blocking out his holy light. Last Sunday our minister preached about how easy it is to crowd Christ right out of our Christmas. There was no room for the holy family in the inn so long ago. In much the same way, in all our holiday bustle and busyness we may leave no room for God’s love in our hearts. Even the best of us occasionally allow the secular to tarnish and threaten to overwhelm the sacred.

So what do we do? How do we make sure we’re not complicit in the darkness that threatens to overcome the light (but cannot, despite our ill will and sloth)? It’s hard to find better advice than this famous verse from Micah:

Do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with your God. (6:8b)

For me, this means not getting too comfortable in our world of materialism and easy excess. Have I been going overboard on gifts for those who already have way too much stuff? Am I neglecting those who have very little? Is there something I can do for a friend, a neighbor, or a stranger that might make a big difference? I need to give where it matters, volunteer where I’m needed. Every day there are chances to show love and compassion. Am I ignoring those opportunities? If I follow through, I’ll do my part to keep the pure light of Christ alive and shining in the world. I’ll try. I’ll drift off the path sometimes, but with God’s help, I won’t wander too far away.